GenX Teenage Gaming Tales: Playing in the Information Desert

Even as someone who witnessed it firsthand, the shift in tabletop roleplaying culture over the last forty years can be difficult to define. But there is one central factor that influences all the other changes. The hobby has changed in so many ways, but perhaps the most profound shift has been driven not from within the hobby, but from the broader social effects of ubiquitous information.

Eighties, I’m Living in the Eighties

When I was playing tabletop RPGs with my high school friends in the early 1980s, information was scarce. And I don’t just mean that there were only three broadcast TV channels in my area, or that if I wanted to research a topic I’d have to ride my bike to the library, look through the card catalogue, and expend considerable time reading books that were almost always out of date. More fundamentally, context about what was happening beyond my directly observable environment was very difficult to obtain.

Put more specifically, because it was really only possible to know what my narrow social group of a half dozen or so close friends was up to, and because it was in most cases impossible to interact with anyone who didn’t live within a few miles of me, my conception of tabletop roleplaying was centered on my friends. Playing AD&D, Top Secret, RuneQuest, and Aftermath! was a group activity, conducted in person. There was no other way to play.

There were no Amazon or DriveThru RPG sales charts, and no Roll20 popularity reports. We had no idea how many people were playing these games in Fresno, Sioux City, Atlanta, or Perth. And we didn’t care, because that information was irrelevant to our enjoyment of these games. It wasn’t as if we could somehow magically play with someone who lived far away.

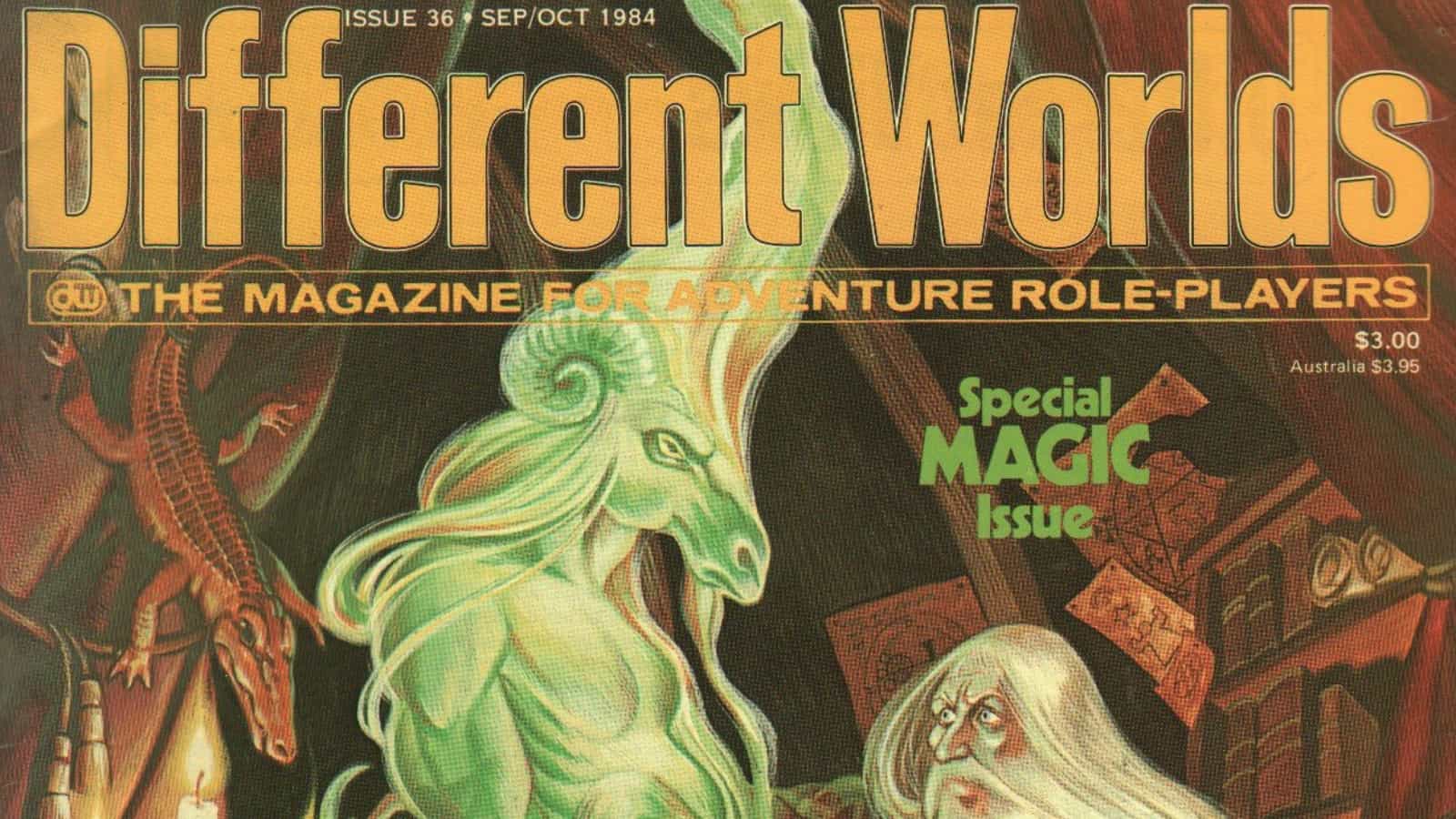

We did know that some games were more popular than others. D&D was always the default, and games that got coverage in magazines like The Dragon, White Dwarf, and Different Worlds, or appeared in the session schedules for the handful of regional game conventions we attended were assumed to be relatively popular. But if anything, knowing that a game we played wasn’t all that well-known became something of a badge of pride for us. Playing Aftermath! in particular, with its insane crunch and anti-heroic premise, was to us akin to listening to a rare British import XTC 45 RPM single.

Secrets

I’ve read that this attachment to the obscure goes hand in hand with a Gen X fixation on authenticity, and there’s probably something to that. My friends and I were generally mistrustful of the dominant paradigm. To us pop music sucked, feathered hair sucked, mall culture sucked. That which was popular was often (but not always – we were as into The Terminator and Aliens as anyone) viewed as inauthentic, plastic, sterile. So we listened to obscure bands, disregarded fashion, and played games instead of going to the mall.

The word obscure bears examination in this context. I’m not sure it’s possible for anything to be obscure any more, at least not for long. Everyone now knows what everyone else is doing. A product or activity or interest can fly under the radar for a while, but eventually it will get noticed and will immediately become part of the Zeitgeist. If three people deep in the Alaskan hinterland are conducting cold fusion experiments using grizzly bear carcasses, it’ll show up on TikTok eventually.

But in the 80s anything that wasn’t broadcast on one of a few TV and radio radio stations, or written about in a newspaper or magazine, could only be discovered through direct, person-to-person word of mouth. In other words, until one of a handful of engines of mass media discovered a subculture, that subculture was obscure to everyone but its members.

On the Outside

Unfortunately these subcultures were often poorly understood and explained by mass media outlets, many of which fed the absurdities of the Satanic Panic. Thankfully that circus of stupidity didn’t really affect my community (another artifact of history: in the 80s the term “my community” meant “where I physically live”), at least from my vantage point. I didn’t know of anyone who wasn’t allowed to play tabletop RPGs, and one of my early gaming buddies was the son of a pretty conservative Mormon father who also happened to be a sheriff’s deputy. He was happy that we spent our time in his garage playing games rather than “getting into trouble,” as he put it.

However, that didn’t mean we advertised our involvement in what were then called “fantasy roleplaying games”. Watching Stranger Things I can’t help but laugh at the notion of wearing game club tshirts. Uh, no. While we were snobbishly proud of the fact that we’d moved on from D&D, and we spent countless hours prepping for and playing games, that didn’t mean we wanted to invite judgment from our classmates.

Sitting around at a table rolling dice and imagining adventures was absolutely uncool. Teenagers may have been savvy enough to understand that there was nothing demonic going on, but tabletop roleplaying was still obscure to those who’d never played one. Therefore it was on some level unknowable, and because it was unknowable, the appropriate teenage response was ridicule. And the best way to avoid ridicule was to keep that fantasy roleplaying business in the group and avoid advertising it to the rest of the world.

Through Being Cool

With this in mind, it may sound bizarre to anyone born after the mid-90s, but the inscrutability of tabletop roleplaying to outsiders was also part of its allure for us. Social groups are defined not just by who is included, but also by who they exclude. My group of friends played tabletop RPGs, and anyone who looked down on that activity or mocked it or at the very least didn’t have an open mind to it wouldn’t be allowed into the group.

We probably would have felt a lot more comfortable had we been able to discuss the Orlanth/Yelm feud or the details of our house rules for armor layering in public without fear of ridicule. But I’m not sure we would have wanted our hobby to be so widely accepted that it didn’t carry some social risk, either.

Ω