What Explains the Market Success of Fifth Edition Dungeons & Dragons?

There’s been a lot of discussion in tabletop RPG circles about just how dominant Fifth Edition D&D has become. It seems to exist as something of a world unto its own, seldom crossing paths with the rest of the hobby. So a discussion about the ramifications of D&D’s current dominance is worth having. But first it’s important to understand why D&D 5e is such a juggernaut. That’s what this post will explore.

With Fifth Edition, D&D Has Never Been Bigger

It’s tempting to chalk up the market success of a product to a single factor, especially if it dominates a niche. But that sort of reductionist thinking limits our understanding of why one product succeeds where others don’t. And if you want to understand the success of Fifth Edition Dungeons & Dragons, you need to examine it in context.

Fifth Edition is an unarguable market success. It is far and away the dominant tabletop RPG globally in sales and mindshare. It’s the de facto tabletop RPG. When people outside the hobby think of tabletop RPGs, they think of D&D. And at the largest game conventions and many game store gatherings, more people play D&D than any other RPG by far.

While it’s impossible to know the exact interplay of factors that have fed the game’s success, there are some obvious candidates. Keep in mind that this is explicitly not an analysis of D&D’s rules. Whether the experience of playing D&D is subjectively better or worse than other games is outside the scope of this analysis.

Familiarity

Dungeons & Dragons leverages the built-in advantage of being the first tabletop RPG, the game that created the tabletop roleplaying industry. It’s been around for almost half a century. While other games from the early days (e.g.,Tunnels & Trolls, RuneQuest, Traveller) still soldier on, D&D is exponentially more deeply embedded in mainstream culture because of its meteoric rise in the late 70s and early 80s.

That early cultural impact is self-reinforcing. For example, the infamous Jack Chick tracts targeted D&D, and the Satanic Panic wasn’t directed at Bunnies & Burrows or Chivalry & Sorcery. The controversy was about D&D specifically, and in the non-gaming public D&D might as well have been the only tabletop roleplaying game.

In its early incarnations the game sold like crazy around the globe, and its cultural impact was enormous. In creative pursuits like writing and film directing you can find many luminaries who played a lot of D&D during that era. More importantly for the long-term success of D&D, the game fueled the development of the computer games industry. The book Dungeons & Dreamers: A Story of how Computer Games Created a Global Industry describes the integral link between D&D and everything from MUDs (Multi-user Dungeons) to the Ultima series, Id Software’s iconic first-person shooters, and MMOs like EverQuest.

Through computer games core D&D concepts became embedded in popular culture. In digital RPGs players assume roles as Fighters, Wizards, and Thieves, exploring dangerous wilderness and deep dungeons with swords in hand, spells at the ready. As they slay more monsters and gain more treasure, they level up, becoming more powerful and capable of taking on bigger challenges. The experience of fantasy computer gaming was bound years ago to the foundational assumptions of D&D. The elements of generic European medieval fantasy fused with D&D’s classes-and-levels framework to form a set of powerful tropes that were absorbed by millions of people who had never even seen a D&D rulebook.

European medieval fantasy served as fertile soil for D&D. The work of J.R.R. Tolkien is often identified as the progenitor of this form of fantasy, but that ignores other important contributors. Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser books, the Dying Earth stories of Jack Vance (from which D&D’s “Vancian magic” originated), Michael Moorcock’s Eternal Champion books (which posited an eternal struggle between the forces of Law and Chaos), Robert E. Howard’s tales of Conan, and the Cthulhu mythos created by H.P. Lovecraft were only some of the works that influenced Dungeons & Dragons.

These books in turn drew inspiration from the Norse and Icelandic sagas, L’Morte d’Arthur, Grimm’s Fairytales, and other veins reaching far back in history. The architects of D&D were steeped in all of it, from the relatively contemporary works of Moorcock to the ancient stories of the Norse sagas. D&D welded all those disparate inspirations together into a whole that was instantly familiar to anyone who had read even just a smattering of fantasy fiction.

As D&D grew popular, its version of European medieval fantasy was reinforced not just through the game itself and its video game offshoots, but also through a Saturday morning animated series and a decades-long run of wildly successful D&D fiction. The Dragonlance series alone spawned over 190 novels – delivering more than 22 million in sales – with translations into multiple languages. In this fashion D&D reshaped fantasy as a whole, cementing its interpretation of the genre in popular culture.

Marketing & PR

Wizards of the Coast (WotC) wisely timed the launch of Fifth Edition D&D to coincide with the game’s 40th anniversary. That rollout tapped into nostalgia and generated initial interest in the broader public. While extant gamers had been waiting to see if Fifth Edition would be a successful response to Pathfinder, people who hadn’t been thinking about or paying attention to D&D for many years were enticed by articles from a variety of highly-visible publications, from Fast Company to the *Wall Street Journal.

The release also coincided with a cultural moment – getting together at a table with friends to roll dice was becoming very popular. Board games were starting to take off in a big way, in part as a response to the power of digital media in our lives. Because of its cultural power, D&D was known even by those who had never picked up a twenty-sided die.

So when Fifth Edition buzz started building, it wasn’t about tabletop roleplaying. It was about the return of D&D. Yes, D&D had been around for decades and had never gone away. But the story was that this new edition was taking the game in a new direction. Parents who had played D&D in their teenage years were buying Fifth Edition and introducing it to their kids. College students looking for something different but familiar were playing it. People who had been playing computer RPGs for years were giving D&D a try. And everyone was welcome to join the fun.

Early D&D was known for being tailored to a target audience of young, straight white men. The infamous harlot table, the frequent appearance of chainmail bikinis, and the uniform whiteness of the game’s heroes didn’t do much to attract a broader audience. But the times were changing, and WotC knew it. The company took a cue from Paizo, the publisher of Pathfinder, a game that took an earlier version of D&D as its starting point and turned it into arguably the most popular D&D variant for a stretch in the early 2010s. Paizo very intentionally made representation important in Pathfinder, and the art and text of the rules reflect this emphasis.

Fifth Edition followed suit, ditching the chainmail bikinis, showing a much broader range of characters, and reaching out to a wider audience. Articles in popular media emphasized this inclusion, and in relatively short order Dungeons & Dragons went from being perceived as the exclusive domain of white dudes to a more expansive and welcoming hobby. And it wasn’t just perception. As Fifth Edition sales took off, it attracted a more diverse audience. While there are no published estimates for other measures of diversity, WotC estimates from 2018 put women at 38% of the game’s audience, in contrast to roughly 10% in the game’s early years.

WotC grew its sales by expanding the addressable market. Instead of just wooing existing gamers back to D&D, Fifth Edition turned a lot of non-gamers into gamers.

But how? Yes, Fifth Edition cast a wider net and it benefited from an effective PR campaign. But that’s not enough to build a new base of younger players. The story of how WotC built up that new audience is an example of how sometimes the best play is to grab hold of a phenomenon that’s already off and running.

The voice actors who starred in the streaming show Critical Role had played D&D 4e and Pathfinder, but decided to run the show using Fifth Edition D&D because they considered the rules more amenable to the livestream format. They chose Twitch because they knew they’d find a young, primed audience.

And find an audience they did; Critical Role episodes have been viewed tens of millions of times, and the show has spawned spinoffs, a setting book, comics, and more. Twitch was such a wellspring for growth because the platform was made for video games, which had for decades been influenced by D&D. Twitch viewers were tabletop-adjacent — they played adventure games, understood the classes and levels tropes born of D&D, and were open to something like Critical Role.

Critical Role wasn’t the first livestreamed tabletop RPG show, but it was hugely influential. The legions of fans who enjoy Critical Role and its offspring don’t all play D&D. It’s likely most of them don’t. But the show has turned some segment of those viewers into D&D players. WotC has pointed to Critical Role and the Twitch platform as a crucial factor in Fifth Edition’s runaway success, and the company quickly threw support behind the show and several others. It organized special one-off livestream events, brought in celebrity gamers, and leveraged streaming as a vehicle for broadening the game’s reach.

Appearances on television, most importantly Netflix’s runaway hit series Stranger Things, have kept D&D in the mainstream consciousness. At the very least, this exposure reinforces its position as the only tabletop RPG with enough cultural heft to be recognized outside the hobby.

WotC has been up front about how they’re marketing Fifth Edition. It’s all about story. Everyone understands story; it’s been with us from our beginnings as humans. Rather than focus on the mechanics of the game, the most popular 5e streams focus on the situations player characters get into, their interactions with each other, and the challenges they overcome.

Network Effects

Every new Facebook user makes the social network more valuable for its existing users. This is known as a network effect — a positive feedback loop in which more each additional user makes the network more powerful. As more people use Facebook, the power of network effects entices more people to join simply because so many people already use it.

Tabletop RPGs are social games that rely to a degree on the same principle, albeit at a smaller scale. In order to play, you need other people (there are solo games but they make up a miniscule slice of the hobby). And if you want to corral other people together to play a game, it’s easier to get everyone to play a game they already know. Many gamers experiment with a wide range of games and welcome the opportunity to try new ones. But getting a group of people to agree on a game can be difficult. The game that has been played by the most players will be more likely to win out and get played, simply by virtue of familiarity.

D&D benefits tremendously from this. Even if Dungeons & Dragons isn’t the favorite game for anyone in a particular gaming group, odds are high that the majority of people in that group have played it. This is even more important in settings where strangers are meeting to play. If you don’t know who you’ll be playing with, familiarity with the game itself makes entering a game less daunting. It also encourages an immediate in-group connection. If you meet another gamer and you’ve both played D&D, you have an instant bond. Like football fans talking about who will win the NFC East this year, D&D players can compare the merits of Paladins and Rangers within moments of encountering each other, whether in-person or online.

The winner-take-all network effect we’re seeing with D&D 5e is a direct result of how we all find out about new cultural phenomena these days. We discover them online, through streams and blogs and podcasts, references in the shows we’re watching on Netflix, and so on. In the early days of what at the time was called ‘Fantasy Roleplaying Games’ players learned about roleplaying primarily through direct contact with friends. But the internet has flattened geography, making network effects that much more powerful; the most popular game will continue to get more popular. Many newcomers only know of D&D. But it also continues to dominate among veteran roleplayers in large part because it’s so well known; even gamers who haven’t played Fifth Edition have likely played a previous version of the game and can easily adapt to the new rules.

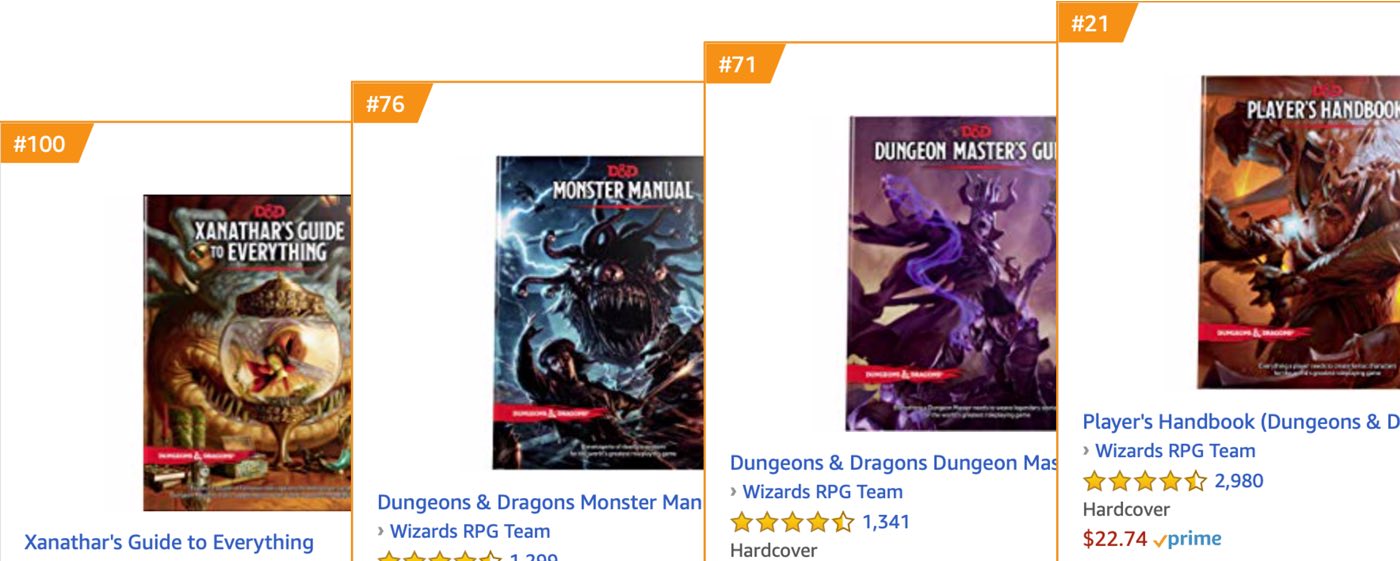

Careful Product Growth

WotC took some flak from existing D&D fans because of the slow pace of initial Fifth Edition releases. The Starter Set, three core rulebooks, and two adventure modules were released in 2014. The following year a campaign guide and two more adventure modules were released. On average thereafter the company has released one or two supplements and two modules a year. By comparison, for Fourth Edition D&D over the course of just three years WotC released two starter boxed sets, eight core rulebooks, 30 supplements, 11 setting books, and 17 modules.

Fourth Edition applied the pattern of the editions that came before it: A boxed set and three core rulebooks followed swiftly by additional core books, modules, and other expansions. That level of support provided plenty of material for D&D fans, but also sent the message that to play D&D meant buying into an ever-expanding series of rule additions.

Whatever other imperatives drove WotC to limit the number of Fifth Edition releases, breaking the cycle of endless splatbooks made it more approachable. Earlier editions had engendered a dynamic in which players who had all the expansion books had an advantage over those who did not. With Fifth Edition, a newcomer can join a table with veteran players and not feel overwhelmed and outgunned.

Conclusion

Whether you think Fifth Edition D&D’s massive popularity is good for the hobby or an obstacle to the success of other games, Dungeons & Dragons is unique in tabletop roleplaying. Its brand power was established in the 1970s & 80s and has grown ever since. D&D has both contributed to and benefited from the popularity of generic European fantasy. The business behind it has learned from previous mistakes and grown a loyal user base. On top of all that WotC is owned by Hasbro — the most powerful company in the tabletop games market — which gives it access to resources smaller publishers can’t match. That’s a potent combination, and Dungeons & Dragons appears unlikely to be displaced as the dominant force in the tabletop RPG market for the foreseeable future.

Ω

[2019-10-22 Further reading: Is Fifth Edition D&D Lifting All Boats ]