Minimum Viable Campaign: Starting

In the software development world, the MVP (Minimum Viable Product) approach has gained mainstream acceptance because it works. MVP dictates that your first release of any software product should incorporate only those capabilities that are vital to the success of the product. By releasing only those key capabilities, you can validate your initial assumptions about what works for customers, get your product to market faster, and avoid wasting time building features nobody really wants.

Managing the development of software projects has made me acutely aware of the power of the MVP approach, and over time I have adapted its core principles to my tabletop roleplaying campaigns. I call this MVC, for minimum viable campaign. MVC is useful because it does three things:

- Recognizes that no GM ever has enough time

- Keeps the GM’s role as the primary driver of the campaign intact

- Gives players the ability to continuously improve the campaign without derailing the GM

Note that MVC explicitly keeps the GM in the driver’s seat. Our Friday night group has experimented with games that shift more of the world building responsibilities to players. It’s an excellent way to streamline prep, and many groups love on the fly collaborative world-building, but it hasn’t worked well for us. My goal with MVC is to stay true to the “GM runs the show” ethos without ensnaring the GM in tar pits of preparation.

The Wrong Way

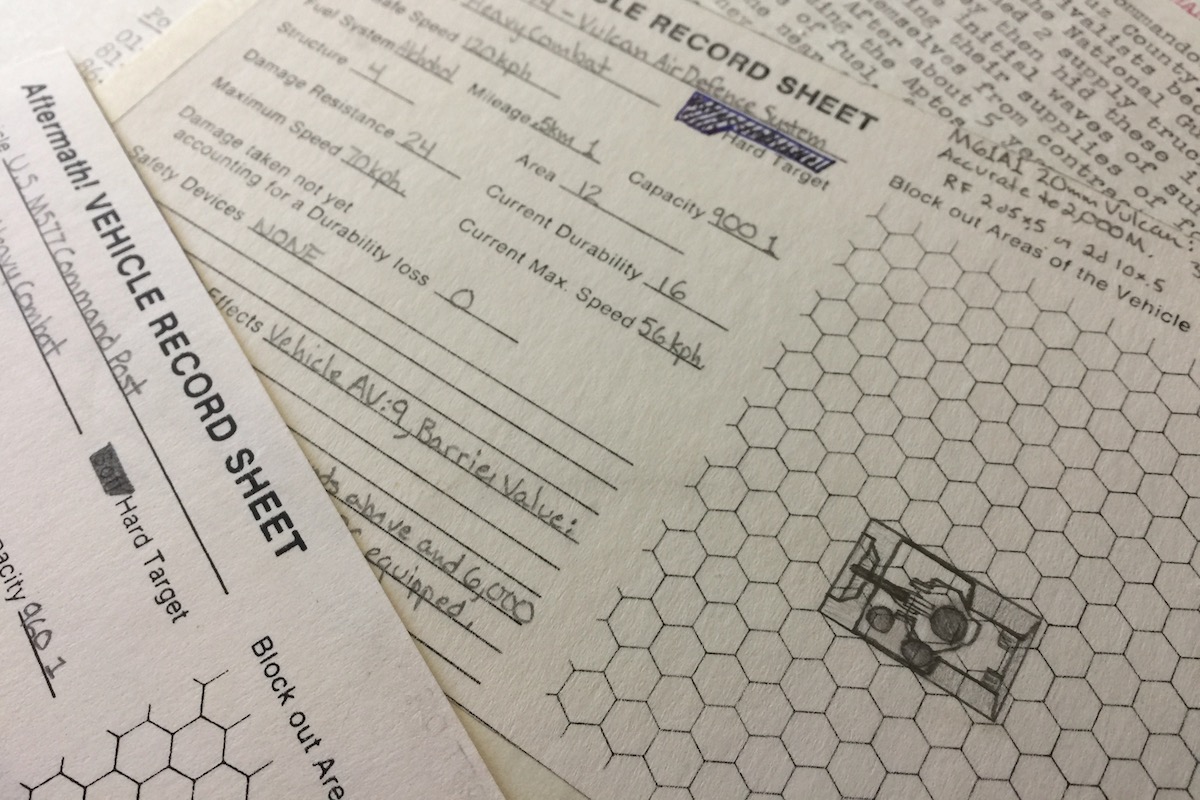

Years ago over the course of a high school summer, I started preparing to run my first Aftermath! campaign. Aftermath! is a notoriously complex game, and I spent much of that time digesting and testing the rules on my own. I didn’t want to expose my players to the complexities of the rules until I had figured them out for myself. In fact, I didn’t expose them to the game at all. I told them I’d purchased Aftermath!, and that I was setting up a campaign. That was it.

After I felt comfortable with the rules, I spent many hours creating detailed campaign notes. I bought 5“x7” index cards and laboriously typed up stat blocks for the myriad factions to be found in the ruins of Santa Cruz, the home town post-apocalyptic setting I was concocting. The Bus Commandos didn’t get along with the Harbor Patrol, and nobody dared enter the Capitola Mall for fear of the mutant rats who held sway there.

The material was all great, at least to me. But all that time and effort I spent filling in stat blocks and creating detailed information about each faction was time I could have spent at the table actually running the campaign. After all, it was summer and we were all teenagers. We all had summer jobs, but we also had oodles of time for gaming.

Additionally, the effort I spent on all those details created a problem for me and for my players, one I didn’t realize until much later. When I was finally ready to start running the game, I had invested so much effort in all those details that one of two things was likely to happen:

- Without consciously realizing it, I would force the players into situations where they would have to confront all those factions I had detailed, precisely because I’d put all that effort into them, or

- If the players resisted my unconscious manipulations and moved the story in another direction, I would feel frustrated and let down, because all that up front effort had been for naught.

Over the course of the campaign, both of those outcomes reared their ugly heads. The campaign was fun, but there was a constant tension between my desire to keep the campaign from going off track and the players’ desire to control their characters. I was railroading the players because I had a meticulously detailed vision of how the campaign should proceed. I wanted to be Stanley Kubrick, and they wanted to be an improv troupe.

The Minimum Viable Campaign

Over the course of many subsequent campaigns, I discovered that the Kubrick approach never worked. Planning every detail before starting play was a waste of time. As work, marriage, and eventually children consumed more and more of my time, I no longer had hours and hours every week to devote to campaign preparation. It was also counterproductive, because it always introduced that tension between GM and player that makes play difficult for even the closest of gaming groups.

Meanwhile in my professional life I found that the Minimum Viable Product (MVP) approach really worked. The foundation of MVP is the understanding that software is not something that you produce, deliver, then walk away from. You never truly know all the variables involved in how customers use the software, how the environment in which it is used will change, and so on. So you validate your concept early, build something that works, deliver it, then keep improving it.

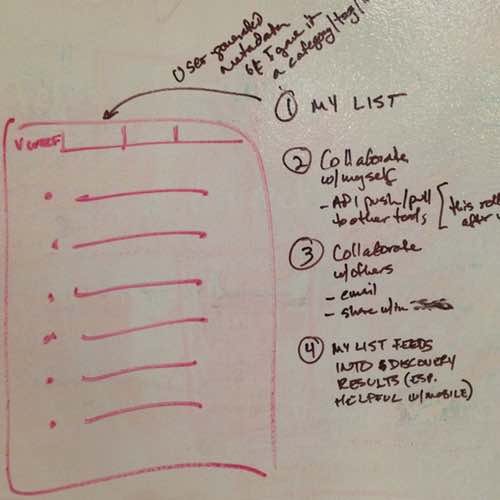

I started using a similar approach to building campaigns. I call it MVC (Minimum Viable Campaign). The key to MVC is to:

- build your campaign concept around player needs,

- deliver enough excitement that the players fall in love with the campaign, and

- continuously improve it by actively listening to your players.

Starting a Minimum Viable Campaign

Answering Player Needs

When I was setting up that Aftermath! campaign I treated it like an in-progress Fabrigé egg that had to be completed before it could be presented to my players. Now when I’m thinking of running a campaign, first think of the players’ needs. What are they looking for in a campaign? What genres and styles do they prefer? What campaigns have been successful in the past, and why? Where have we gone off the rails before, and what should I avoid this time around?

Our Friday night group enjoys fast-paced action, but is also really big on character development. In general we prefer small-scale combat and gritty situations where the characters have to think their way past more powerful opponents. Our campaigns tend to include plenty of ethical dilemmas, and we’ve had success with games like Star Wars and Call of Cthulhu that pull directly from movies and books.

With those thoughts in mind, I came up with a super short campaign outline that defined:

- the setting,

- broad themes and style of play

- types of characters and adventures it will include, and

- the game system we’ll use.

Finally, I took note of what makes the campaign concept awesome, and what it will not be.

I then took this outline to the players to see what they thought of it. My pitch to the players was essentially:

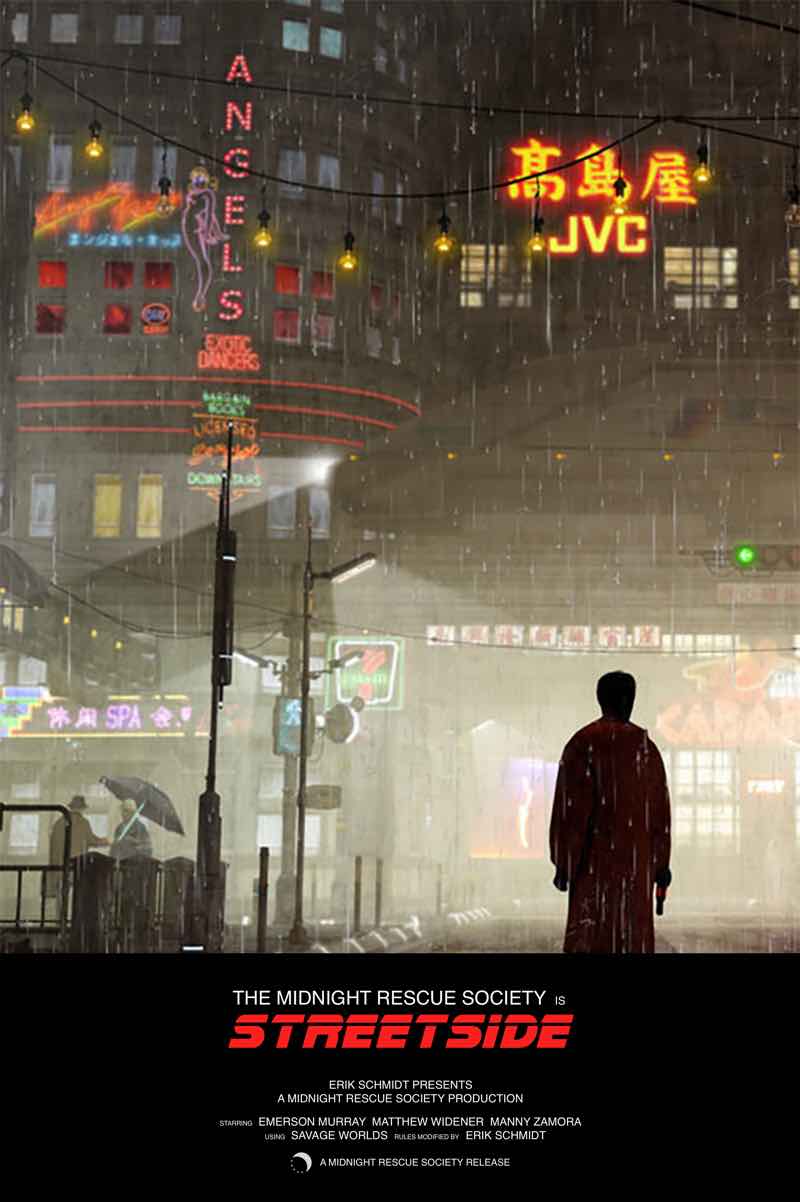

The campaign takes place in the Los Angeles of Blade Runner, a few years before the movie. There are Replicants, but no Nexus 6 models yet. You will be part of the first group of Blade Runners deployed by the police department, and they’ll be hunting down escaped Replicants. We’ll use only the movie as canonical source material, but I will be building out from that.

Also, it won’t be a cyberpunk game. It will be a Blade Runner game. The movie is essentially a noir detective tale. Technology and its implications for humanity are central themes, but technology plays a minor role in the plot itself. There is no jacking in. There are no razorboys and corporate mercenaries. This is not Cyberpunk: 2020 or Shadowrun with the magic cut out.

What will make this campaign special and set it apart is the emphasis on hard boiled detective noir rather than on technology. There will be combat, but when it happens it’ll be deadly, and the you’ll need to rely on their wits.

The players were excited by the concept, and as we discussed it further we honed the themes and style. We all agreed that the primary underlying theme would be exploring what it means to be human, and the boundaries between Replicants and humans. They also let me know that if I had any ideas for big twists or revelations that took the campaign in new directions as it progressed, they were fine with me doing that. They figured it was in keeping with the subject matter of the movie, and they felt it would make the campaign more exciting and keep them on their toes.

It took some mutual exploration to land on a game system. Originally I was leaning toward One Roll Engine, as we’d just used it in another campaign we’d just wrapped up. But ultimately we went with Savage Worlds because of its simplicity and pulp feel, which seemed best suited to the pacing and tone we wanted for the campaign.

Note that as GM I include my needs as well. It’s no good to come up with a campaign concept my players can embrace but I won’t enjoy. I discovered this the hard way with Spirit of the Century. It’s an excellent game with rules that fit the genre, excellent writing throughout, and one of the best GM advice sections you’ll ever find. But even though my players thoroughly enjoyed character creation and dove right into the game, I was a flat-footed GM. I just couldn’t get into it.

Why? Because the pulp genre has never been one of my favorites. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t shoehorn myself into it. I was familiar with many of the tropes, but that wasn’t enough for me to build a fantastic setting. As a GM, you can’t own and truly master the setting if you don’t love that setting. And if you don’t love the setting, you won’t enjoy running the campaign.

Blade Runner is one of my favorite movies. I’ve read Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner and seen Dangerous Days: Making Blade Runner. That doesn’t make me a Blade Runner expert, but it’s an indicator that I’m not going to tire of the setting any time soon.

Initial Preparation

MVC doesn’t mean no prep. But instead of going into exhaustive detail on every aspect of the campaign, it’s important to focus on what players will make contact with immediately. So instead of laying out the lineage of the five kings who came before the current ruler of your world, and the backstory of the nine Houses of Royalty, think about what the characters will be doing in their first session.

For our Blade Runner campaign, I thought about the Los Angeles we see in the movie. We don’t see much of it, really. We know it’s a sprawl. We know it’s colder and wetter than the real Los Angeles, and we can surmise that the future lies in the off-world colonies, not in the grime and grit of Los Angeles.

So I created a very brief backstory:

- There are several districts in LA, and we only saw bits of the downtown area in the movie

- Some of these districts are populated by refugees, many of them from Europe

- There was a war in Europe some time in the last couple of decades, hence the large population of recent refugees

- During that war there were limited nuclear exchanges that contributed to the climate effects seen in the movie

- There was no concerted effort to address pollution, and it also has a profound effect on climate and weather

- The Tyrell Corporation is not just a powerful company, it is one of a handful of the most powerful corporations on the planet

- Corporations involved in the colonization of the off-world colonies are also very powerful

- Replicants are not allowed on Earth except in certain circumstances, but recently some of them have been returning illegally from the off-world colonies and causing havoc

- The LA police have assembled a group of about two dozen detectives to form the Blade Runner unit. They are tasked with finding and capturing (or retiring) Replicants who show up in LA.

- The player characters are part of this group, as is a laconic detective named Rick Deckard. They report to Lt. Bryant, a has-been determined to climb his way up the rungs of power within the department.

I also wanted to put just enough meat on these bones to be ready when the players take the game in an unforeseen direction. So I created a short list of locales and jobs, just to get a sense of where scenes might take place and who would inhabit them. This seemingly prosaic exercise helped me discover things about the setting without resorting to elaborate backstory.

For example, there’s no public Internet akin to what we have now, but the technology for programming incredibly complex Replicants is available. So I posited that there are private networks controlled by corporations. Individuals can gain access to some parts of these networks by paying through the nose for the privilege at businesses roughly equivalent to today’s Internet cafes.

I revealed most of this background information to the players in the Slack channel we use for the campaign, and they told me about their character concepts. As we discussed those concepts, a couple of them were adjusted until we had a three-person team that felt like an interesting mix of capabilities and personalities.

Discussing the characters and their motivations is critically important. While players can’t (and shouldn’t) be expected to know how their characters will react to situations before they unfold, knowing what those characters want is vital. In this case one of them is a careful, cultivated professional intent on moving up the chain of command. The second harbors a grudge against Replicants because of events in his past, and he is a bit unstable because of it. The third is intent on uncovering the truth, no matter where it may lead him.

At this point the players were on board with the concept, they had characters they were ready to play, and they had enough of an understanding of the setting to be prepared for the first session. I also made it clear that they would be learning more about the world along the way, and that they should ask questions whenever they needed more info.

Next Step: Putting the World Into Motion

Stay tuned! In my next post I’ll describe how to define what’s happening around the player characters, how to create an engaging initial adventure, and how to create memorable NPCs for your minimum viable campaign.

Ω