Words to the Wise: Worldbuilding Through Dialogue

Still a Little Whimsical in the Brainpan

Recently I rewatched Serenity because, well, why not? One of the most delicious things about Firefly and Serenity is the economy with which they transport viewers to a distinctive imagined future. The backstory is minimal. There are no elaborate factional conflicts. The ships and sets aren’t terribly unique, and most of the planets look like Bronson Canyon. So how does the setting feel so alive?

Dialogue is the secret ingredient.

First, occasionally a character will say something in Chinese. We don’t even need to know what it means (and it may be better when we don’t) to recognize that this is a different future. A little goes a long way.

Second, every once in a while you hear something in the dialogue that makes sense but requires a half-second to parse. It’s all of a kind – specific words put together in a way that evoke the Wild West. Whether people actually spoke that way in Nevada City in 1881 is beside the point.

The Wild West is engrained in our collective memory; its echoes are everywhere in global pop culture. So when we hear Mal declare “I am to misbehave,” or Shepherd Book reckon something, that’s all our brains need to conjure up all sorts of associations with the Wild West. This evocation of the Wild West serves another purpose as well. It separates the denizens of the scruffy Outer Planets from the citizens of the sanitized Alliance.

So in the Firefly/Serenity universe, how people speak is as important as what they’re communicating to other characters. This recognition got me thinking about other works I admire that similarly leverage dialogue.

Mark You That and Noat You Wel

Riddley Walker takes effort to read. It doesn’t require Name of the Rose historical-references-in-three-languages level effort, just basic parsing of the text. Working your way through the words is like encountering a thick regional accent. After at time you pick up on its rhythms and you come to understand what’s being said.

First published in 1980, Riddley Walker is written from the perspective of its titular protagonist, a boy living in what might be called a Scrap Iron Age in “Inland” (England) two millennia after a devastating nuclear war. Everything about the setting and its inhabitants is different from what we as readers know.

So the author, Russell Hoban, didn’t adjust a few words here and there – he changed the spelling of familiar words and applied a particular cadence to the narrator’s delivery:

- “Stil it takes you strange walking in your old foot steps like that. Putting your groan up foot where your chyld foot run nor dint know nothing what wer coming.”

- ”I tried to plot the parbeltys of that and program what to do nex.”

That reconstruction of language, combined with the details of a society alien to our own, make reading Riddley Walker a uniquely immersive experience.

But because the book relies so much on the spelling of words, and a full lexicon of terms highly bound to history and terrain, there isn’t much of direct practical value we as role-players can apply from its use of language. I still heartily recommend Riddley Walker for its own sake, and as an example of how powerfully dialogue can shape a fictional world.

An Ordinary Bone Bunch

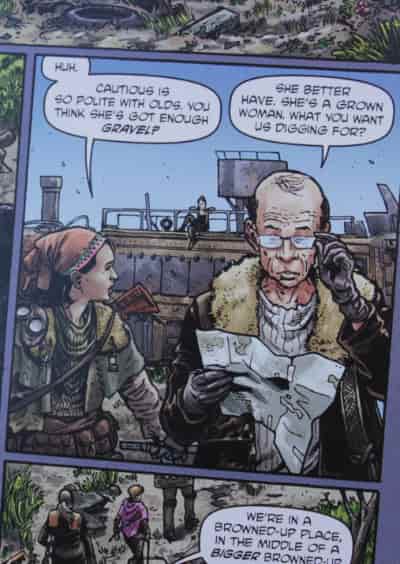

The Crossed Plus One Hundred comics are post-apocalyptic tales of a far different stripe. They portray fledgling civilization rebuilding in Tennessee a century after an “Infected” outbreak almost wiped out humanity. These Infected are a manifestation of humanity’s worst impulses. They engage in depraved, wanton violence and make the walkers of The Walking Dead seem relatively benign by comparison.

As you might expect, enduring that kind of collective trauma marks survivor culture. How can foul language be considered offensive in a world that has gone completely off the rails? Famed writer Alan Moore exposes this through dialogue. For example, “fuck” is already a famously multipurpose term, but a hundred years after a zombie apocalypse, it’s lost any shock value and is used simply for emphasis.

Unlike the Firefly/Serenity universe, the language of Crossed Plus One Hundred evokes history – that which came after ”the Surprise” and that which came before it. This is because the story connects the past to the present. So the words characters use need to keep reminding us of those connections. In Firefly/Serenity, the use of archaic language is used for thematic purposes, rather than to explicitly support the story.

There’s much about the power of dialogue to be learned from Crossed Plus One Hundred. It’s also a lot more involved than what you find in Firefly/Serenity. While a cheat sheet would do to keep track of linguistic differences in that universe, more effort would be required to make sense of it all. Critically, more effort would be required at the game table. Even the most ardent method actor would have to put a lot into it. So as with Riddley Walker I enjoy the Crossed Plus One Hundred comics, both as artistic works on their own merits and as inspiring worldbuilding examples, but I wouldn’t attempt to embrace their level of linguistic drift in a roleplaying campaign.

Were You Born or Egg-Hatched?

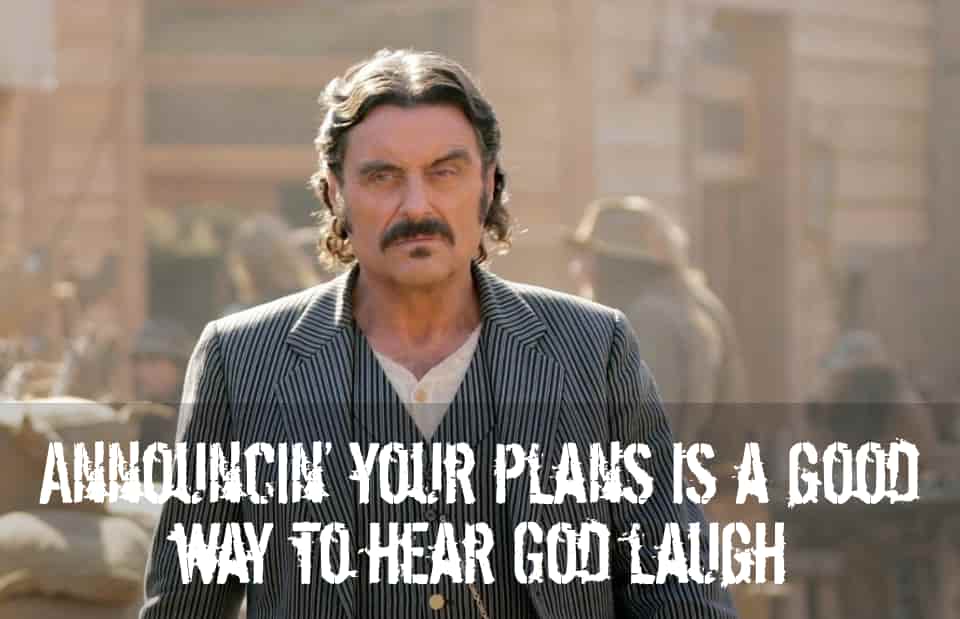

Firefly/Serenity uses anachronistic terms to evoke the spirit of the Wild West, and Crossed Plus One Hundred normalizes crude language to reveal how much horror humanity has endured. Deadwood, written primarily by David Milch, uses dialogue informed by the rough-and-tumble Dakotas of the 1870s. If you’re offended by dirty language, you’ll bounce right off Deadwood. But what fascinates me most about the show’s dialogue is how it combines vulgarity with wit.

The denizens of Deadwood are not society’s winners. These are not well-heeled highbrow East Coast landowners. They are almost all taking a shot at success in this lawless frontier town because they feel they have no other options. They speak the language of people accustomed to bad breaks, tough choices, and bitter disappointment.

Deadwood is a dangerous place, a pit of conflict, but none of its inhabitants are two-dimensional, and a vein of dark humor flows through Deadwood. Consider this exchange between Swearingen, the town’s unelected boss, and Dan Dority, his chief henchman:

Dority: “I’m older, and I’m much less friendly to fuckin’ change.” Swearengen: “Change ain’t looking for friends. Change calls the tune we dance to.”

Again we find ourselves looking at (and listening to) a work of art that is inspiring for many reasons, among them its ability to build a world with words. And again it’s a bit much to emulate in a roleplaying campaign, either for GMs or players.

Slot and Run, Chummer

Now is the moment in this little tour when I fess up. I’ve left dialogue untended for quite a long time in my gaming. It embarrasses me to say this, but I haven’t seriously engaged with lexicon and dialogue since the early 1990s.

At the time my original gaming posse and I were converting our long-running in-person Shadowrun campaign to a form of play-by-post in which I as GM would write the players into difficult situations, they’d write themselves most of the way out, and I’d wrap it all up in a conclusion. As part of that conversion process I collected slang from the multitude of Shadowrun supplements I owned, and made a slang sheet to help us write better dialogue. It was a multi-page affair that took several hours to compile, but it proved quite useful as a writing aid.

Eventually the play-by-post campaign ended. Real life got in the way, and for a few years my only interaction with tabletop RPGs was reading rulebooks and pining for the good old days. When I got back into gaming it was at first infrequent. The full-on immersion of the Shadowrun days was a thing of the past.

Later I found a new gaming group, discovered lots of new games, started learning new tricks, and built deep campaigns. But I never put much thought into the day-to-day speech patterns of the characters I played. Now that it’s on my mind, I just have to bring it into my games.

Was That the Primary Buffer Panel?

My biggest takeaway from this little journey is that the words characters use can be a powerful tool in establishing setting and evoking themes. Inspiration is all around us – Valley Girl, Lock, Stock & Two Smoking Barrels, Clueless, Idiocracy, and many more examples provide similar lessons.

As a practical matter, however, even the Shadowrun cheat sheet I created would place an undue burden on actual in-the-moment roleplaying. A handful of terms, a few undefined references here and there are enough to transport us from the table (or or screens) to an alternate world without turning game night into a language immersion class.

It seems Firefly/Serenity approach in most cases should be just about right. Now if you’ll excuse me, I have a (brief) Degenesis slang sheet to write.

Ω